March 19, 2023

I taped a new YouTube history video on Friday and this is what I talked about.

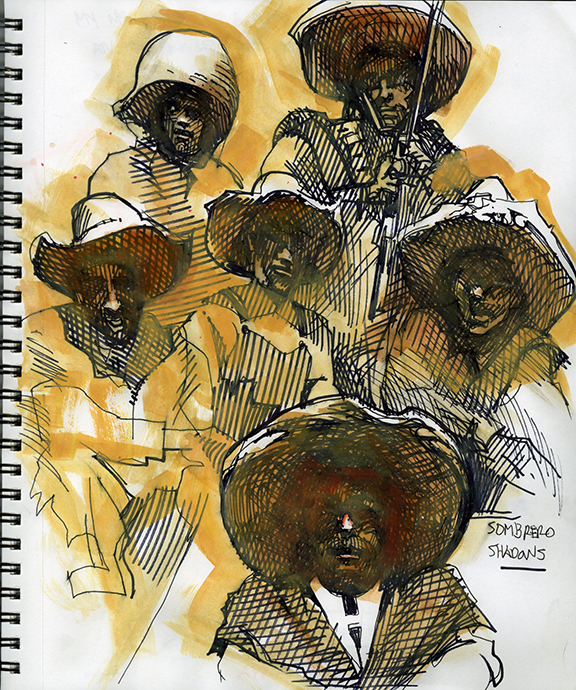

Why Isn't Black Bart More Famous?

He robbed more than 30 stagecoaches while Jesse James robbed maybe six. So why isn't Black Bart more famous in the annals of the Old West? Let's take a closer look. The reasons just might astound you.

About twenty years ago, I was in San Francisco with my honey and I went into one of my favorite Old West haunts. That would be the Argonaut Book Store at 786 Sutter Street where they not only have a ton of old musty, first edition books on the American frontier, but more than a few classic, original photographs. In fact, I bought a pristine, original carte de visite of Lotta Crabtree for $200 which I still keep next to my desk in the studio.

And yes, this was the inspiration for my cover painting for "Hellraisers & Trailblazers: The Real Women of The Wild West"

Whole Lotta Love Quad

Anyway, back to the Argonaut, while I was looking around for something else, my wife Kathy said, "Look at these photographs of Wanted men carried in the saddlebags of a California sheriff." I scrunched up my nose and said, "No, thanks." The former Moon Mountain Elementary school teacher said, "Pray tell, why?" And I said, "Because they look like urban criminals." Perplexed, she then asked, "Do you mean to tell me if they were wearing bigger hats and looked like cowboys, you would be interested?" She had a good point, and I replied, "Right as rain, Roy."

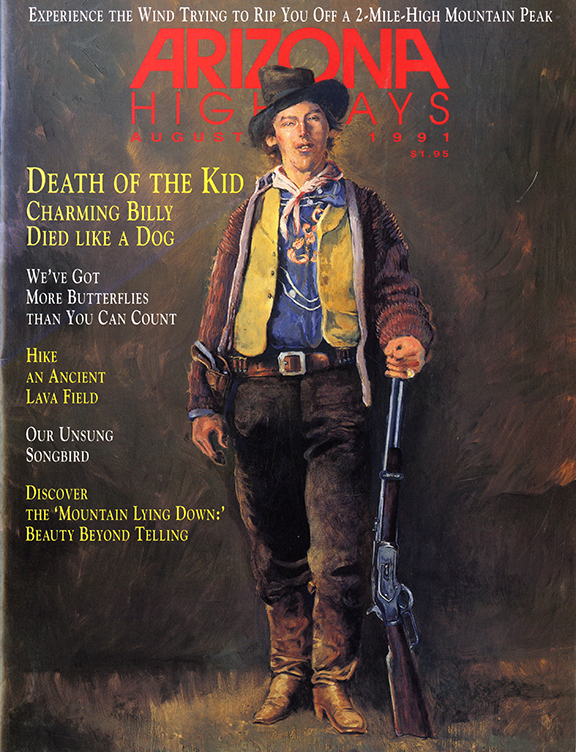

This, perhaps, more than anything else, explains why the notorious stage robber, Charles Boles, alias, Black Bart, has never really captured the imagination of those of us who love the Wild West. True, he's very well known but think about this: there have been 67—and counting—movies about Billy the Kid and north of 37 movies on Jesse James and the same for Wyatt Earp, but there is only one film on Black Bart. Why? Because he looks like a dapper dude, not a daring cowboy. He's a city slicker, and an old one, at that.

Dapper Charles Boles, alias Black Bart

And, here's another problem: Black Bart walked to and from his robberies! Think about that. He pulled off a whopping 32 stage robberies in his storied career. He robbed 29 stages before he was captured in 1883, then after his release from prison in 1888 we think he robbed three more before he disappeared completey. That's a lot of walking. In one suspected hold up he allegedly walked 250 miles!

Black Bart's Ingenius Motus Operendi

Most bandits in the Old West rode horses to and from their robberies. Of course they did. It's what we expect. Not Black Bart. He often took the ferry from his headquarters in San Francisco to Oakland, then he hopped on a train to, say, Sacramento, and from there he would walk the rest of the way to the robbery site. In one robbery, he carved mock gun barrels out of wood and stuck them in the bushes, pointing at where he knew the stage would stop. When the stage appeared he would walk out into the center of the road in front of the lead horses and say, "Throw down the box." If the driver got cute, Black Bart would say, "Don't shoot Boys," looking over at the fake gun barrels, "until I say so." That cowed more than one brave reinsman. That is just crazy amazing, and clever, and it's what allowed him to escape time after time as posse after posse went looking for a mounted man. You can imagine they must have ridden right by him more than once and he probably just smiled as they rode on oblvious to his clever ruse. But even this, his counter-intuitive genius, robs his image of being a daring brigand. So, perhaps this is why there is only one movie about him. Here's what my good friend, John Boessenecker has to say about the film.

"In 1948 the film Black Bart was released, starring Dan Duryea as the slippery stagecoach robber. Like most Hollywood westerns, it was fiction and had little to do with Black Bart except for its title. In this rendering, Boles is an outlaw who abandons his gang, goes to California, and embarks on a spree of stage holdups. Finally he stops a coach that happens to carry his old bandit partners as well as the famed performer Lola Montez, played by the sultry Yvonne De Carlo. Bart and Lola form an attachment, and following a series of improbable adventures, he is killed by a posse. The film was a success and revived so much interest in Black Bart that the following year Wells Fargo Bank offered a reward to anyone who could prove what happened to the mysterious bandit. The reward was never paid."

—John Boessenecker

In real life, Boles served a six year sentence for the last robbery only, then was released for good behavior after four years and two months, and then he pulled off three more stagecoach robberies and vanished, for good. This also does not make for a good movie story. No resoution to sink our teeth into.

Here, once again, is author John Boessenecker, on what he speculates happened to Boles:

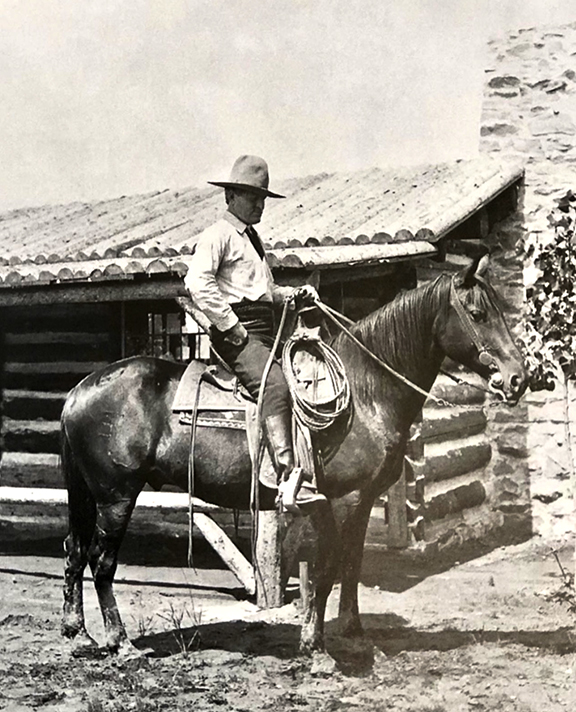

"In 1903, a newspaper in Santa Rosa, California, reported that Boles 'was in Arizona or New Mexico, aged and respected, his identity not known, a man of family in affluent circumstances, an extensive stock range being his realm.' This could also be dismissed as another wild yarn, except the newspaper provided some accurate details about Boles’s background and said that its informant, who lived in Santa Rosa, had been a fellow volunteer in the 116th Illinois. That man was undoubtedly Charley’s friend Dr. Joseph Hostetler, the surgeon for the 116th, and it is possible that Boles wrote to his old Civil War comrade and boasted of the success that had so long eluded him. So, did Black Bart use his stolen loot to acquire a ranch in the American Southwest or in Mexico? Did he live out his final years in quiet anonymity as a prosperous cattleman? Surely that is how Charley Boles would have wanted his story to end. Perhaps some day the truth will out, but until then, the fate of Black Bart, the poet highwayman, remains one of the great mysteries of the Wild West."

—John Boessenecker, author of "Gentleman Bandit: The true story of Black Bart, the old west's most infamous stagecoach robber"

But John believes Boles commited an even worse crime:

"Mary Boles never wavered from her firm conviction that Charley would come back to her. In another letter she sent to the San Francisco Chronicle, Mary insisted, 'I am convinced that he never thought of deserting me when he left Montana for California after the most severe struggle against the drought of that year and the one before. As to him not sending money to us, he well knew I would rather suffer want than be supplied with a dollar that did not come honestly.' But Mary’s beliefs were simply delusional. Her blind faith that he would return was based entirely on the empty promises in his letters. Charley’s correspondence revealed him as a selfish, manipulative liar, for Mary and her daughters never saw him again. And that was the greatest crime he ever committed."

—John Boessenecker

And, the lawman who tracked him down. What does he think of the prolific stagecoach robber?

“In the popular mind, Black Bart, as he so romantically styled himself, has come to be regarded as a sort of modern Robin Hood, a stage robber of heroic mold, a gallant free lance, who never robbed the passengers or the poor, but confined his attentions entirely to wealthy corporations such as Wells Fargo & Co. This is a delusion. He is, in fact, the meanest and most pusillanimous thief in the entire catalogue, for by his own statement he made all his large hauls from the mail, which he always rifled, and from which, excepting his last robbery, he always obtained more than from the express. . ."

—James Hume, the detective who busted Boles for the 29th robbery based on the handkerchief laundry mark he left behind

So, in conclusion, Black Bart was too dapper, too old and too clever for his own good, at least when it came to his outlaw image.

“Authenticity is about being true to who you are, even when everyone around you wants you to be someone else.”

– Michael Jordan